Twitter’s iconic blue bird has faced strong headwinds in recent years, ultimately succumbing to Elon Musk’s takeover and being swiftly rebranded to X. But this is not the only avian social media mascot that has had to navigate an impending demise. The bird’s yellow counterpart, the face of Koo, which was to be India’s answer to Twitter, has now suffered the same fate.

After 4 years of operations, Koo’s co-founders Aprameya Radhakrishna and Mayank Bidawatka have announced that the social media app is shutting down citing the lack of a financially viable path forward. In this article, we will trace Koo’s journey from its first flight to its soaring prominence and eventually a brutal plummeting.

Taking Flight

Koo was a COVID baby, first emerging in March 2020 and swiftly gaining popularity as it won the government’s Atmanirbhar App Innovation Challenge. Positioned as a desi alternative to Twiiter, the app described itself as a platform “built for Indians to share their views in their mother tongue and have meaningful discussions.” Its key USP was regional language support. The founders saw a gap in the social media market with most social products being English dominant despite the fact that 80% of the global population spoke a language other than English as their mother tongue. They wanted to “democratize expression and enable a better way to connect people in their local languages.” The app was initially launched in Kannada, later adding support for Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Assamese, Marathi, Bengali, Gujarati, Punjabi, and an assortment of foreign languages as well.

Koo provided a similar user interface to that of Twitter, allowing users to categorize their posts with hashtags and tag other users in mentions or replies. In its launch year in 2020, Koo saw 2.6 million installs from India, compared to 28 million installs for Twitter. However, the app’s moment in the sun came in early 2021 when a standoff between Twitter and the Indian government led to a surge in Koo’s popularity.

Turbocharged by Turbulence

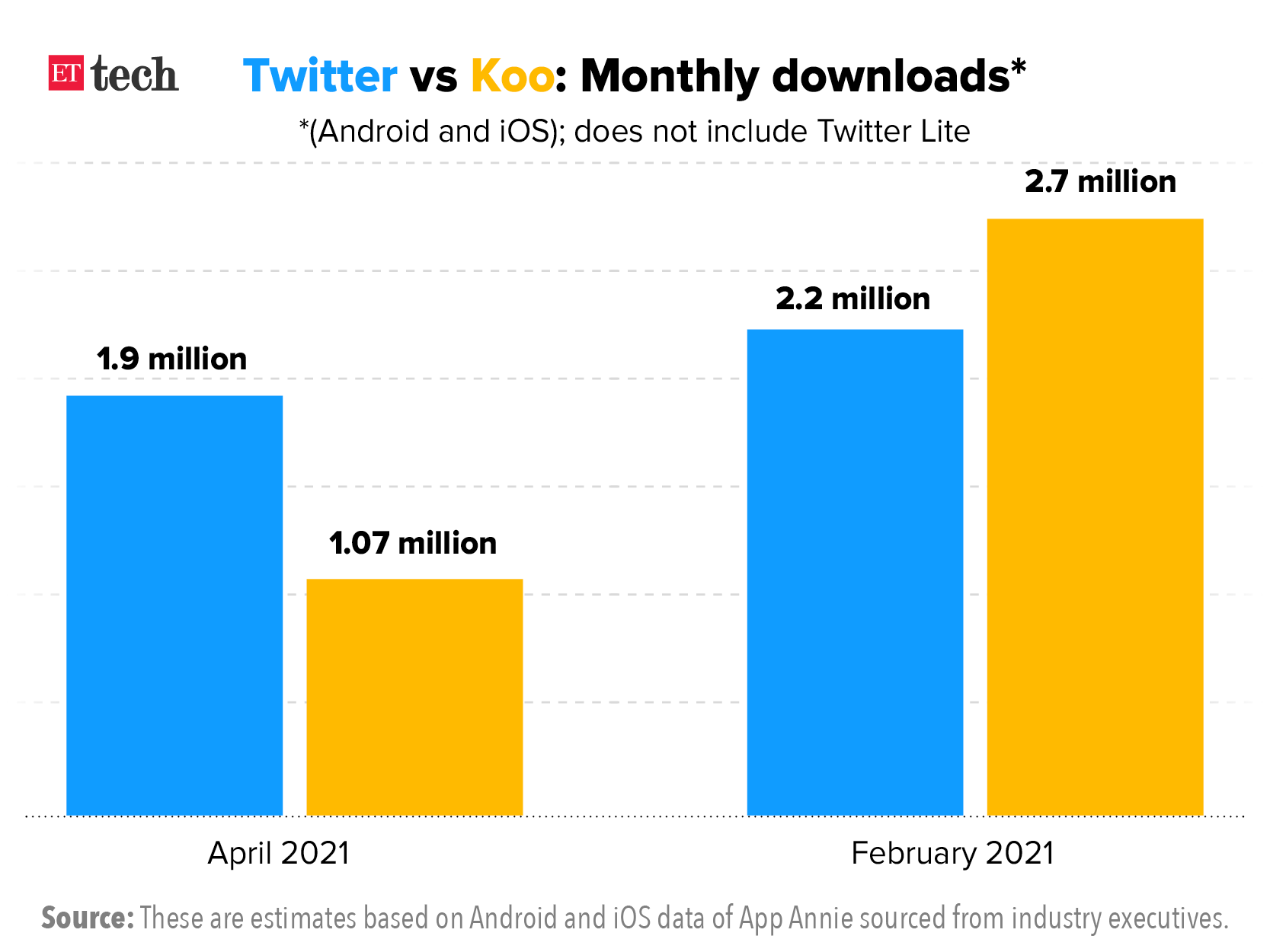

Following the decision by the Parliament to pass a series of controversial agricultural laws in September 2020, protests erupted all over the country. Things came to a head in Feburary 2021 when the Indian government ordered Twitter to block the accounts of hundreds of activists, journalists, and opposition politicians, which it believed were spreading misinformation. While Twitter complied with most of these orders, it also refused some on the grounds of freedom of expression. This rankled the government and its loyalists with high-profile Cabinet Ministers such as Piyush Goyal, various government officials, and BJP supporters boycotting Twitter and setting up accounts on Koo instead. Koo reported a whopping 2 million downloads that month, up 4x from the month prior.

Koo, in fact, benefitted from political instability in other regions as well. Later that same year, Twitter found itself in hot water in Nigeria when it deleted a tweet by Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari. Twitter claimed that the tweet which threatened a crackdown on regional separatists in Nigeria was in violation of the platform’s rules, but did not provide clarity on what those rules were. In response, the Nigerian government banned Twitter in June 2021 and opted to set up its official account on Koo instead. That again led to a surge in popularity for the Indian upstart with Koo clocking in 1.9 million downloads that month, its highest since February of that year.

Source: ET Tech

Source: ET Tech

In November 2022, Koo again emerged as a Twitter alternative, this time in Brazil. With Twitter’s popularity taking a hit following the announcement of Elon Musk’s acquisition and the reinstatement of Donald Trump’s account on the platform, users globally were looking for alternate social media platforms that more aligned with their political ideologies. While more established Twitter competitors such as Mastodon and Hive were the go-to platforms for most of the western world, Brazil, curiously, opted for Koo. Close to a million users downloaded Koo in a single week that month, marking the platform’s greatest window of growth.

At that time, Koo reported having 50 million users worldwide. The yellow bird from Bangalore looked set to soar towards global domination. What could go wrong?

Grey Skies and the Inevitable Fall

Everything that could go wrong, did go wrong. Even though Koo enjoyed these spurts of popularity, the fundamentals were never really in place for Koo to truly challenge Twitter.

The rise in popularity in Brazil was not due to any inherent qualities of the platform, but merely an in-joke as the word “koo” is a homphone for a Brazilian word for “ass.” During the Koo craze in Brazil, a popular celebrity influencer from the country having over 15 million Twitter followers even tweeted out, “My goal is to have the biggest koo [ass] in Brazil,” and linked to his Koo account. The fad, and Koo, died down in Brazil almost as quickly as it had started.

Even the surge in Nigeria was short-lived as citizens went back to Twitter as soon as the government lifted the ban on the app.

Back in India, Koo struggled to monetize its user base. While it experimented with various revenue models, including advertising and premium subscriptions, it failed to achieve any sort of financial sustainability. The platform’s dependence on venture capital funding became a point of concern.

Following its initial popularity surge in India in February 2021, Koo had raised $4 million in Series A funding. It used the funds to build a team to help support the growing user base but the tech costs alone added up to $3 million for the company in FY22. Even though they had raised a further $30 million in May 2021, a staggering 60% of that was spent on advertising and promotion with the company aiming to double down on its popularity and drive more app installs. To put that into context, Twitter only spent 6% of its expenses on marketing and promotion.

User acquisition is one thing; Koo also struggled with user retention. Twitter’s success lies in its addictiveness. For all the controversy on what Twitter does and does not allow on its platform, it is this very controversy that has helped Twitter thrive. Just 25% of Twitter users are responsible for generating 97% of all tweets on the platform, highlighting the joy of just watching the world burn from the sidelines. Koo’s intentions of creating a much more tranquil and agreeable environment free from drama, although noble, missed the fundamentals of what drives the social media business, for better or worse. As a result, users never really saw Koo as an alternative to Twitter, but as an alternate world altogether.

The final nail in Koo’s coffin was the funding winter that gripped the startup ecosystem in 2023. That coupled with a dwindling user base meant that Koo could not attract any investors. The flow of capital dried up and the company was ultimatley forced to lay off 30% of its workforce.

Over the last 12 months, Koo had explored partnerships with multiple larger internet companies, conglomerates and media houses in a last-ditch attempt to stay alive, but no prospective buyer bought the idea of Koo that the co-founders were selling.

In the farewell post on LinkedIn, the co-founders mentioned that ‘we are entrepreneurs at heart and you will see us back in the arena one way or another’. Industry insiders indicate that Aprameya and Mayank have already begun work on a consumer tech project with a small team on a bootstrapped budget. Having already faced prior setbacks with Vokal, a Q&A platform they had launched before Koo, this new venture will be a test of their entrepreneurial resolve.

Back to the Drawing Board

Koo’s story is the latest in a long line of Indian entrepreneurs reinventing the wheel. Some of the biggest startups in the country today are imitations of global peers. Ola and Rapido are the Indian versions of Uber and Lyft while Zomato and Swiggy are knock-offs of GrubHub and DoorDash. While bringing global products and services to the Indian market is commendable, the fact that the Indian versions of these companies are plagued by much of the same business-model issues faced by their Silicon Valley counterparts show that lessons have not been learned.

Creating a scalable local product is an arduous journey. It requires immense patience, a penchant for innovation, and someone with deep pockets to finance the road from 0 to 1. The Koo co-founders summarized this quandary well in their farewell post, “Patient, long-term capital is essential to build ambitious, world beating products from India – be it in social media, Al, space, EV or other futuristic categories. It will need a lot more capital when the space has a global giant already. And when one of these companies takes off, it can’t be left to the whims of the capital market, which goes up and down. It needs a strategic outlook to safeguard it and make it thrive. These aren’t to be looked at as profit-churning machines in two years from launch. They need to be nurtured for a larger long-term play. We would love to see that long-term view for large bets from India.”

The yellow bird of Koo may have been grounded, but it won’t be long before another Indian startup takes the flight of fancy, aiming to soar to unprecedented heights, trying to breach the increasing level of expectations in the startup ecosystem.

____________

Written By: Nimesh Bansal